You must have heard of hard drives (HDDs) or solid-state drives (SSDs). Some of you might have even used the term “memory” to call them both, and you’re sort of correct. But things are more complicated than that.

This post will explain digital storage and how it works in a computer system. Among other things, you’ll find the differences between HDDs vs. SSDs and SSD variants, such as SATA SSD vs. NVMe SSD.

When you’re through—that’s if you didn’t get bored and give up halfway—you’ll, among other things, know how digital storage works, buy your next SSD (or hard drive) with confidence, and even brag with your friends or loved ones about how cool the whole thing is.

Most likely, you’ll be somewhere in between. And that’s still a good enough place to be in this case.

Dong’s note: I originally published this post on February 22, 2018, and updated it on March 14, 2025, with additional relevant information.

Digital information in brief

We live in the Information Technology (IT) age, where we store and exchange information digitally. It’s “digital” because it involves digits. More precisely, two specific digits.

The binary way of information coding

In the computer world, information is stored and processed using strings of zero (0) and one (1) in different patterns. This method of information coding is known as binary coding, or digitizing.

Tips

In a nutshell, you can understand binary as the count limit.

Generally, in daily life, we all have taken for granted a base-10 system, called decimal, in which we count from 0 to 9. We put some of those digits together for any higher value, such as “one” and “zero” for 10 or “two” and “one” for 21, etc. With binary, we count from 0 to 1. So to convey two or more, we have to put 0 and 1 together in specific patterns.

Mind you, we have other less common counting systems: the base-60 system for time and the base-12 (duodecimal) for, well, eggs. Now you get the idea.

The more information we need to code, the longer these strings are. And they get long really fast.

For example, “Dong Knows Tech” (no quotes) is a short phrase of text, but to convey it in binary, we have the following string (which varies depending on what application you use to code):

01000100 01101111 01101110 01100111 00100000 01001011 01101110 01101111 01110111 01110011 00100000 01010100 01100101 01100011 01101000In other words, that’s how the computer “sees” that phrase. If you change the color of the text or use the site’s logo up top, the string will get even longer, and we’ll need different software to code and decode it.

More information, such as a photo or movies, requires many, many more zeros and ones of complex patterns. But, just like counting with decimal numbers, there are infinite possibilities. We can use those two digits to capture everything as long as we have the appropriate software for the job.

Using binary to communicate is impossible for humans—we’d fall asleep. But for the machine, that’s the most efficient way. It has only two possibilities (zero or one), and an average computer can handle trillions of binary calculations per second without ever breaking a sweat. (It does become warm or even hot but that’s a different story).

Tip

Digitalization means using computer software to convert information (texts, images, audio, videos, etc.) into binary strings for easy storage and exchange and translating it back into the original form when needed for on-demand consumption.

Digitalization also makes information extremely compact. A solid-state drive (SSD)—as big as a little finger physically—can hold the amount of data equal to the text of an entire average-size library’s books. And it’s much easier to send digitalized information than to ship actual books—we can move information around much faster.

But before that, the information has to reside somewhere. Specifically, before you can read this beloved “Dong Knows Tech” phrase, the browser has to know where to pull that crazy string of digits above from and where to show it. And that brings us to “memory” and “storage” and their differences.

Memory (RAM) vs. storage (HDD/SSD)

A computer has two hardware parts that hold information: RAM, short for Random Access Memory, and a storage device, often a hard drive or a solid-state drive.

Let’s start with RAM.

RAM: It’s volatile

RAM holds information that’s being processed. Everything you see on the screen right now is floating within some RAM stick. The more RAM a computer has, the more information it can process simultaneously.

By nature, RAM is speedy compared to general storage, but this type of storage device itself comes in different speed grades and standards.

Regardless of which type of RAM you use, it allows the information to be flexible and malleable. For example, when you scroll a web page, the text and pictures move up and down instantly, and using some particular software, you can make changes to a photo, a movie, a document, etc.

The gist is that the information that’s being manipulated in real-time resides in RAM. Manipulated by whom, you might wonder? In a computer, that’s the job of the central processing unit, often known as the CPU.

In return, everything in RAM is temporary (or volatile)—this type of environment needs electricity to keep the information “alive”. If you unplug the computer, information in RAM is lost, which is why you need to save your document before turning off the computer.

Saving a document means you move the information from RAM to a storage device.

Storage: It’s persistent

There are many forms of digital storage but HDDs and SSDs are the most popular and the noly we’ll cover here. However, no matter which type of storage device you use, they all share this attribute: Non-volatility.

Specifically, information stored on a storage device remains even when you unplug the device from power. The next time you use it, such as turning on your computer, you’ll find the previously saved document intact.

A computer’s storage device holds more than just your documents. It also contains the operating system and all software applications. When you turn the machine on, it loads all that into the memory (RAM) and creates a virtual environment where you can send/receive, consume, or manipulate information.

Tip

Digital storage is like books, magazines, or scrolls—the information they contain is always there.

RAM is the part of our brain where temporary ideas, feelings, or imaginations float as we experience the world through our senses, like reading a book or viewing a painting. To keep those ideas alive, we need to write them down.

The faster the storage device, the less time the software needs to move information between it and RAM, which is part of a computer’s “performance.” The higher the capacity, the more information a digital storage device can store.

And that brings us to the hard drive (HDD) and the solid-state drive (SSD), the two most popular forms of digital storage.

HDD vs. SSD: Similarities

From a user’s perspective, a solid-state drive and a hard drive behave the same: They store information and make it available when a user needs it.

HDDs first became available in the late 1950s and have undergone many changes. SSDs—the flash-based type we use—are much younger and have been widely known to consumers only since about 2010.

The popular SATA connection type

In the beginning, an SSD is simply a faster alternative to an HDD, or a different type of hard drive.

That’s because SSDs are initially based on HDDs by sharing the same interface called serial AT attachment (SATA), which is the most popular in consumer-grade computers. Being SATA-enabled allows SSDs to replace HDDs seamlessly—without extra hardware or software requirements.

The SATA interface has two prominent designs: 3.5-inch (for desktop computers) and 2.5-inch (for laptops). Although SATA-based SSDs are only available in the latter form, they work in all applications where any hard drive fits.

SATA is currently in its third revision (SATA 3), with a top speed of 6 gigabits per second (6Gbps) or 750 megabytes per second (MB/s), which is the ceiling speed of any SATA-based SSDs.

The future of SATA

There likely will not be a newer and faster version of SATA in the future. That’s because SSDs have been increasingly popular and more affordable, and they have unique designs and interfaces that deliver significantly higher speeds—more below.

As SSDs’ speeds get faster, the SATA connection standard is the bottleneck, and the growing popularity of SSDs will eventually render SATA obsolete.

Since 2018, there have been more and more notebooks without SATA support, opting for much faster interfaces explicitly designed for SSDs and other high-bandwidth applications.

HDD vs. SSD: Differences

First and foremost, SSDs are significantly faster than HDDs. It’s safe to say that even the fastest hard drive is slower than the slowest SSD.

On average, a SATA SSD will have at least twice the sequential (copy) real-world speed of a SATA hard drive. However, SSDs’ strong point is their random access performance, which contributes more to a computer’s general performance.

On the inside, an SSD and an HDD are different in principle. Let’s start with HDDs.

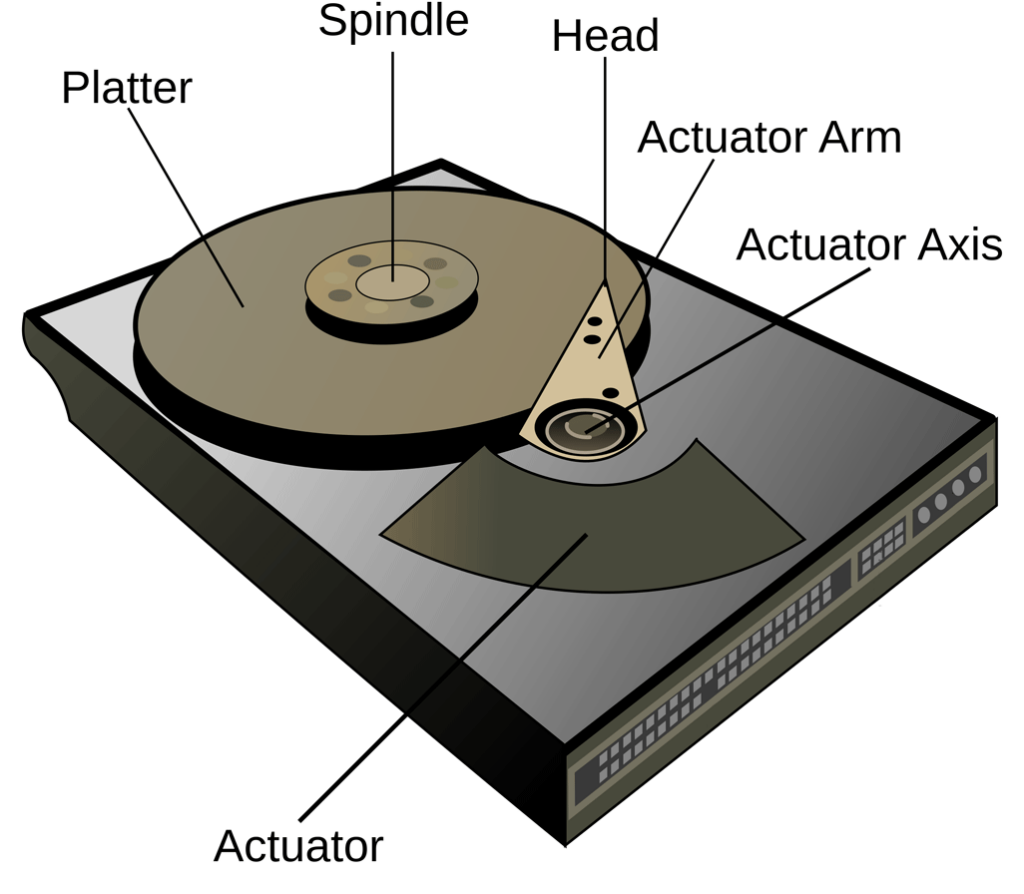

Hard drives: Mechanical machines

Open up a hard drive; you’ll find a few platters stacked on top of one another like a spindle of compact discs. The more platters a hard drive has, the more information it can store.

Each platter’s top and bottom surfaces contain multiple circular paths in concentric rings, called “tracks.” The drive’s read/write head, which hovers on top (and bottom) of each platter, can magnetize these paths into binary patterns to store information.

This process is the same when you write the first time or any subsequent times (overwriting). In either case, the drive magnetizes each portion of the platter, called sector, directly into the patterns required at the time of writing, regardless of their state.

A hard drive’s reading/writing speed depends mainly on how fast it can spin its platters. Most consumer-grade HDDs spin at either 5,400 or 7,200 rounds per minute (RPM), while high-end hard drives can spin at 10,000 RPM.

Hard drives are a technological marvel

Even though hard drives are on the way out among consumer-grade applications, each of them is a mechanical marvel on the inside.

Specifically, the read/write head hovers within a few nanometers from the platter without ever touching it.

If you enlarge a hard drive to the size of a football field, the platter would be the game area, and the head would be the size of a golf cart. Now imagine that little cart is moving at about a million miles per hour, just a hair above the ground.

It’s already amazing if it doesn’t touch the ground every few minutes. And it (almost) never does.

More on Hard Drives: SMR vs. CMR

As mentioned above, the more platters a hard drive has, the more information it can store.

Generally, storage makers achieve higher storage capacity of hard drives by increasing the number of platters and the density of each platter’s track.

That brings us to different ways data is recorded on a hard drive.

Conventional Magnetic Recording (CMR)

The first type is called “Conventional Magnetic Recording” (CMR)—some companies might call it “Perpendicular Magnetic Recording” (PMR).

With CMR, each data track on a platter doesn’t overlap the adjacent ones—there’s a gap between them.

CMR allows for straightforward recording. It generally fills up each platter the drive track by track, which is simple and fast. But we lose some space for the gaps between tracks. This means more materials are rquired and CMR drives tend to be more expensive.

Shingled Magnetic Recording (SMR)

Since 2015, there’s been a new way of recording on a hard drive called “Shingled Magnetic Recording” (or SMR).

The name comes from the fact that each data track overlaps its previous one, similar to shingles on a roof, eliminating the gaps between tracks and increasing the density of each platter a great deal. SMR hard drives are more affordable.

In return, when the computer writes to an SMR hard drive, the drive picks where it wants to put information randomly. After that, when idle, it reorganizes the data. As a result, an SMR drive is much slower than a CMR counterpart when you write a lot of data simultaneously. It also works all the time—even when the system is idle—meaning it won’t last as long.

Over the years there have been lots of improvements in the world of the mechanical hard drive, especially in terms of storage space. Nowadays, you can find a single hard drive with tens of terabytes. That plus the fact they are getting more and more affordable, and we need more and more storage space, the hard drive will never go away

Solid-state drives: It’s a complicated world

An SSD has no moving parts. It’s an integrated circuit that uses less energy yet can provide much faster access to the information it stores than an HDD.

It also can come in much smaller physical sizes and doesn’t necessarily need to conform to a standard design. Still, most SSDs do come in particular design anyway for ease of use reasons. There are also proprietary form that fits only in a particular application—like a smartphone or the case of most Apple laptops whre the SSD is soldered on the machines’s main circuit board.

The world of SSDs can be quite complicated due to the nature of the technology. The first thing you should know is that you can only write so much to an SSD, and there’s no “overwriting”, either.

Finite P/E cycles

Except when the SSD is brand-new, writing to an SSD always means erasing existing information from memory cells and programming them with new binary patterns.

For this reason, writing to an SSD is often referred to as a program/erase (or P/E) cycle. It’s pretty similar to writing on a whiteboard with a Sharpie—unless the board is brand-new, you’d always need to clean it before you can draw something new.

And just like a whiteboard that won’t last forever—eventually, you’ll wear out its surface—an SSD also has a finite number of P/E cycles. You can only program a memory cell so many times before it wears out and becomes unreliable.

And programming information on an SSD is a complicated and inefficient process by nature.

Blocks and pages

An SSD organizes its memory cells in pages and blocks, with one block containing many pages. Here’s the problem: An SSD writes page by page but erases block by block.

As you can imagine, if you want to write more pages to a half-used block, the SSD will first need to copy the good pages (those with valid information) to a different place, erase the entire block, then write back the good pages together with the new pages onto that block.

As a result, an SSD has to write more, even a lot more, than the actual amount of information you need to write, which brings us to half a dozen interesting technical terms.

SSD-specifics terms

To understand SSD well, you must have all of these terminologies in your vocabulary.

Write amplification

As mentioned above, the term refers to the phenomenon that an SSD has to write more than the amount of information the user needs to write.

The higher the write amplification, the shorter the drive’s life span.

Garbage collection

A process where an SSD needs to reallocate pages of a block before erasing the entire block so it can write on that block, as described above.

The more efficient garbage collection is, the faster a drive can write.

Over-provisioning

An SSD can dedicate a part of its storage (typically 10%) to make garbage collection more efficient.

That’s like having an extra room in your house to store stuff temporarily when you need to do a major cleanup.

As a result, many SSDs don’t have full capacity. For example, 256GB or 512GB drives only have 240GB or 480GB of actual user-accessible storage space.

TRIM command

TRIM is an actual command of an operating system and not an acronym.

The command notifies the SSD when a page of old data is no longer valid—the garbage collection will skip it during the reallocation. When enabled, TRIM helps reduce Write amplification a great deal. In fact, without this command, an SSD can run out of writes within a matter of days, so it’s important to make sure TRIM is enabled—the default case of most operating systems.

Endurance and wear-leveling

Endurance is the amount of data you can write to an SSD before it becomes unreliable.

To increase usability, SSDs use wear-leveling, algorithms that make an SSD use up all of its memory chips, cell by cell, before the first cell is erased and written on again. That’s similar to using all parts of a whiteboard evenly instead of picking just a particular corner like we generally do in real-life.

Wear-leveling ensures the SSD “wears” evenly. Thanks to this, SSDs with larger capacities generally have higher endurance than smaller ones.

Of all the items above, endurance is likely the most important since it decides the value of a drive. Let’s find out more about it.

SSD endurance

SSD endurance is generally presented in two ways: Terabytes Written (TBW) or drive writes per day (DWPD).

Terabytes written

TBW is the total amount of data you can write to an SSD over its life span before it becomes unreliable. The higher the TBW value, the better the endurance and the longer the drive will last.

It’s important to note that TBW can be misleading since larger capacities generally mean a higher TBW rating. For example, if you compare a 4TB low-endurance SSD against a 1TB high-endurance SSD, the former will have a higher TBW value.

For this reason, there’s another more consistent measurement for endurance.

Drive Writes Per Day

DWPD is the number of complete drive writes per day over the SSD’s warranty period, which tends to be between three and five years.

For example, if a 250GB SSD has a 1 DWPD rating and a warranty of three years, you can expect to write up to 250GB daily and every day for three years. If the same drive has a DWPD value of .5, you can write 125GB to it per day for the same period, and so on.

The higher the DWPD value, the better the endurance, but remember that DWPD needs to be weighed against the warranty period. For example, a drive with .5 DWPD over three years has lower endurance than one with .4 DWPD over five years.

The endurance anxiety

Since the write on SSDs is finite, we tend to worry a lot about their longevity. In reality, though, chancers are there’s no need to worry at all.

Even though you can’t write to an SSD forever, with normal usage, it’d take many years to deplete even a low-capacity SSD’s P/E cycles. Most of us don’t write more than 10GB per day to a drive, and many days we don’t write anything.

Considering SSDs have become more affordable in pricing and larger in capacities, endurance is no longer a huge issue. Still, if you still want to extend the life span of an SSD, then reduce any unnecessary amount of writing you do to it. Reading does not affect a drive’s life span.

SSD types: NVMe SSD vs. SATA SSD

Over the years, there have been many standard designs (form factors) of SSDs. That’s not to mention that most Apple computers use proprietary SSDs—the pool of SSD shapes and sizes is so large that hardly anyone can remember them all.

The classification of SSDs is also confusing because the form factors (designs, physical shapes), the interfaces (how a drive connects to a host), and the speed standards overlap between different types.

For example, SATA is both an interface and a speed standard. There are also standard SATA and mSATA form factors, and mSATA itself is another interface variant of SATA.

Higher-end NVMe SSDs come in different types, too. There are also proprietary SSDs, like those found inside most Apple computers.

That said, strictly from the interface point of view, you only need to know two popular types: SATA and M.2. I’ll explain the form factors and their speeds.

SATA SSD

The SATA standard has been in use for the past few decades and is currently at the third revision—SATA 3—which has a cap speed of 6Gbps (or 750MB/s). In real-world usage, the fastest SATA SSD, after overheads, has the top sustained copy speed of around 550MB/s

SATA SSDs come in two main designs:

Standard SATA: Standard SATA SSDs share the same design as laptop (2.5-inch) hard drives, though most are slightly thinner than 7mm, compared to 9.5mm of the HDD. Here are the current best standard SATA SSDs you can buy.

mSATA SSD: Short for mini-SATA, mSATA is a variant of standard SATA with a much smaller form factor and uses a different interface (called mSATA) to connect to a host. mSATA is a transitional form factor and has largely become obsolete since 2017.

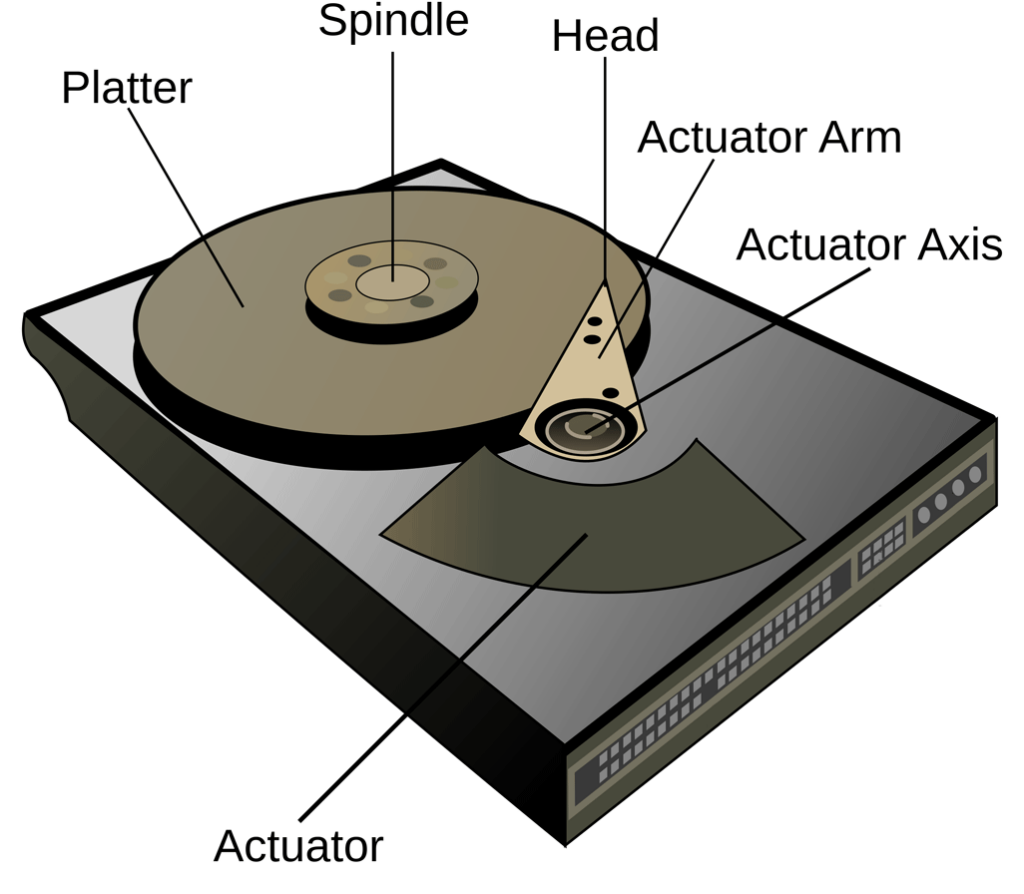

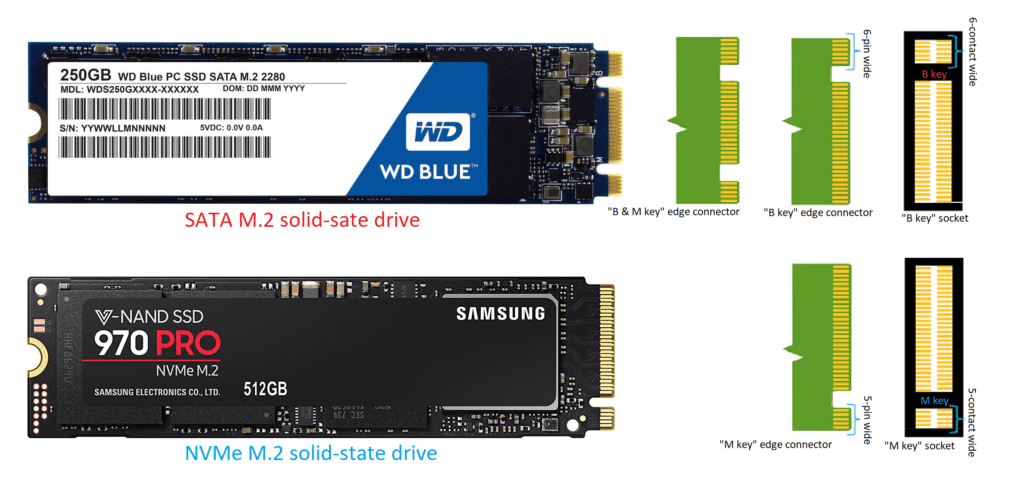

M.2 SSD

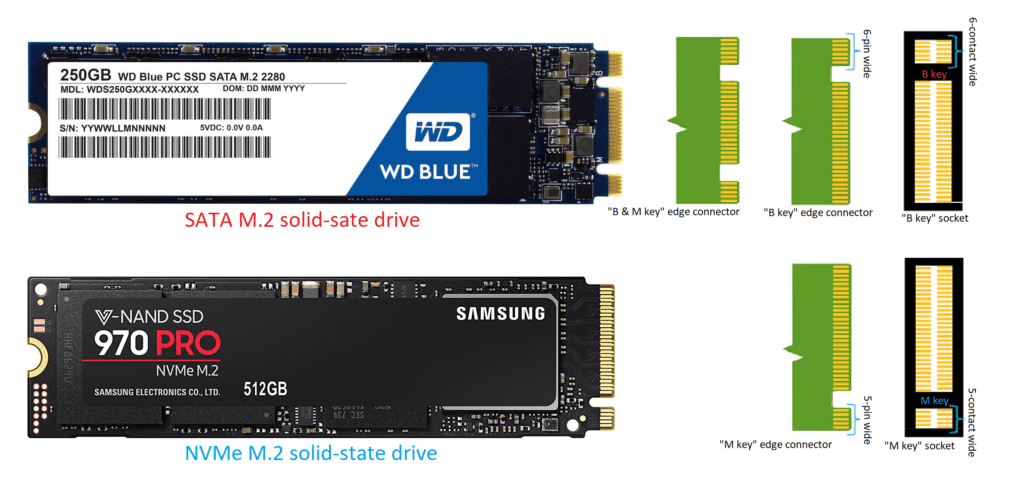

M.2 is the latest interface with the highest number of design variants via different lengths and “module keys.”. M.2-based devices are designed to fit into the M.2 slots on a motherboard (or can be added to a computer without this slot via a PCIe adapter.)

M.2-based SSDs are super compact, about the size of a gum stick, and have similar thickness. They are 22 mm wide with various lengths. Specifically, M.2 SSDs come in the following size and module keys:

- Length: Varying from 30mm to 110mm, though most M.2 SSDs use the 2280 design, which is 22mm wide and 80mm long.

- Module keys: The key determines an M.2 device’s connector or how it connects to a host (like a computer motherboard). There are A-key, E-key, B-key, and M-key. The first two are used mainly in Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and cellular cards. M.2 SSDs only use B-key and M-key.

| Module key | Device Measurements (width+length in mm) |

Bus speed/interfaces | Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| B | 3042, 2230, 2242, 2260, 2280, 22110 |

PCIe x 2 (up to 16Gbps), SATA (up to 6Gbps), |

Wi-Fi/Bluetooth/Cellular Adapters, SATA SSDs, PCIe x2 SSDs |

| M | 2230,2242, 2260, 2280, 22110 |

PCIe x4 (up to 128Gbps) | SATA SSDs, PCIe-based (NVMe) SSDs |

All variants of M.2 SSD have even smaller physical sizes than mSATA. They are so small that people tend to call M.2 devices “sticks” or “cards.”

M.2-based SSD: B-key vs. M-key (SATA M.2 vs. NVMe M.2)

The M.2 keys are where it gets confusing. M.2 SSDs are always super compact but not necessarily faster. The speed depends on their interfaces.

In the early days of M.2 SSDs, most drives used the SATA speed standard for compatibility reasons. This type is transitional and is not faster than standard SATA SSD. For this reason, it has slowly faded into obscurity in the past couple of years.

Modern M.2 SSDs use the PCIe interface, which is tens of times faster than SATA. This type is called NVMe SSDS. However, PCIe itself has different revisions and different performance grades.

But first, here’s the break-down of M.2 SSDs:

- Original versions of M.2 SSDs use the B-key. They tend to use SATA speed standards and are not faster than regular SATA SSDs. Some B-key M.2 drives use the 2x PCIe speed standard and are slightly faster. These drives only fit in the B-key socket on a host (like a motherboard).

- Some M.2 SSDs use B & M keys to fit in both B-key and M-key sockets. These drives also tend to use SATA or x2 PCIe speed standards.

- The latest M.2 SSDs always use the M-key. These drives use x4 PCIe (or faster) speed standards and are the fastest SSDs on the market. They are known as NVMe drives—more below.

If you get an M.2 SSD today, it’s likely an NVMe drive with an M-key.

M.2-based SSD speeds

M.2 SSDs have a few (and growing) speed variations.

Speeds of SATA-based M.2

SATA M.2 drives have the same speed as regular SATA SSDs (6Gbps). Sometimes, you can find the same drive in two different form factors, like the WD Red SA500 SSD case.

Speeds of PCIe-based M.2

Again, M.2 drives that use PCI Express (PCIe) lanes to communicate with a host computer are labeled as NVMe (Non-Volatile Memory Express) M.2 drives.

As a result, they have much faster speed than SATA SSDs and will get even faster in the future with new generations of PCIe, as shown in the table below.

Specifically, a PCIe Gen 3 has a top speed of 8Gbps (985MB/s) per lane. That said, a PCIe Gen 3 x2 (two lanes) M.2 drive has a cap speed of up to 16Gbps. Similarly, a PCIe Gen 3 x4 SSD has a ceiling speed of up to 32Gbps.

| PCIe Gen |

Commercially Available | Rate per lane (rounded) |

x1 Speed |

x2 Speed |

x4 Speed |

x8 Speed |

x16 Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2003 | 2 Gbps | 250 MB/s | 0.5 GB/s | 1.0 GB/s | 2 GB/s | 4.0 GB/s |

| 2 | 2007 | 4 Gbps | 500 MB/s | 1 GB/s | 2.0 GB/s | 4 GB/s | 8.0 GB/s |

| 3 | 2010 | 8 Gbps | 984.6 MB/s | 1.97 GB/s | 3.94 GB/s | 7.88 GB/s | 15.8 GB/s |

| 4 | 2020 | 16 Gbps | 1969 MB/s | 3.94 GB/s | 7.88 GB/s | 15.75 GB/s | 31.5 GB/s |

| 5 | 2022 | 32 Gbps | 3938 MB/s | 7.88 GB/s | 15.75 GB/s | 31.51 GB/s | 63 GB/s |

Note: 1 Gigabyte per second (GB/s) = 1000 Megabyte per second (MB/s) | 1 Gigabit per second (Gbps) = 125 MB/s

In my experience, a good PCIe Gen 3 NVMe SSD (like the Samsung 970 EVO) can deliver sustained copy speeds of over 2,000MB/s.

NVMe SSDs have consistently gotten faster and faster, thanks to the faster lane speed of next-generation PCIe. A PCIe Gen 4×4 SSD, such as the Samsung 980 PRO, can deliver a rate some 50% faster than a PCIe Gen 3 drive and PCIe Gen 5 SSD, such as the Crucial T705, can deliver over 4000MB/s of sustained copy speeds.

But there’s only so much faster performance that can make a difference. In my experience, starting with PCIe Gen 4×4, the speed of NVMe SSDs has reached the point where faster would produce only a light meaningful performance improvement. That said, PCIe Gen 5×4 is likely the last practical application for this type of consumer-grade storage.

PCIe NVMe SSDs are generally backward compatible. A PCIe Gen 5 drive will work with a PCIe Gen 4 and Gen 3 M.2 slot, and vice versa.—PCIe Gen 3 SSDs will work with a Gen 4 or Gen 5 slot.

The takeaway

When it comes to consumer storage, NVMe SSDs are the way to go. All new motherboards and laptops now use NVMe as the standard internal storage choice and many even come with multiple M.2 slots.

However, the hard drive won’t disappear. In fact, it has just become more relevant than ever with the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), which requires lots and lots of cheap storage space. Western Digital’s move to focus on platter-based storage is a testament to this.

For the home, the hard drive still provides low-cost storage solutions, such as NAS servers, where speed is not the priority.

No matter what type of storage you use, in the end, it’s always what you have to convert into those zeros and ones that matters. So, maybe work on your life story, yes?